The spring and summer of the 1964 election year moved on two tracks, which was to be the historical paradox of Lyndon Johnson’s presidency: Vietnam, where Johnson was flailing; and his domestic “Great Society,” ambitions that were a genuine, deeply felt priority.

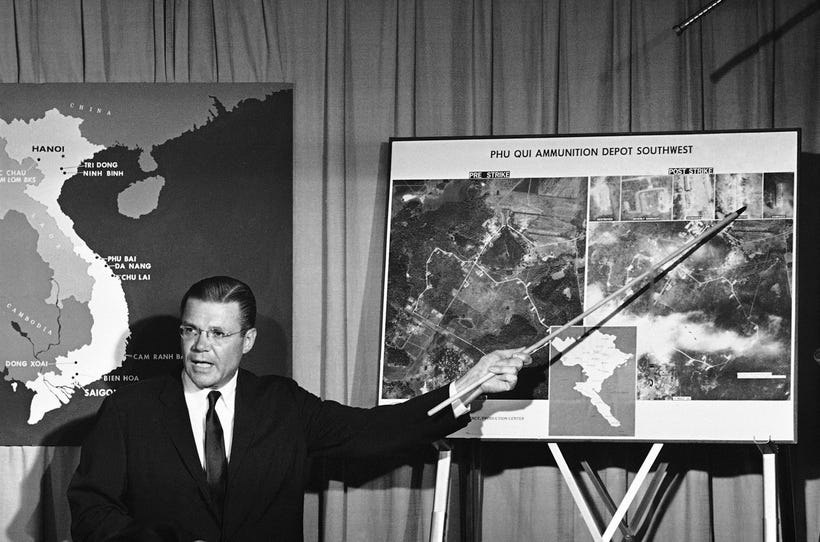

“Amid all this uncertainty and frustrating confusion, I made an impulsive and ill- considered public statement that has dogged me ever since,” Robert McNamara writes in a particularly revealing passage in his memoir. At a Pentagon briefing on April 24, this was the answer when a reporter said that Senator Wayne Morse of Oregon, a staunch critic of the administration’s Vietnam policy, had called the conflict “McNamara’s war.”

“I am following the President’s policy,” McNamara responded. “…I must say [in that sense] I don’t object to its being called McNamara’s War. I think it is a very important war and I am pleased to be identified with it and do whatever I can to win it.”

Less than a week later, talking to Johnson, McNamara’s tone was altogether different. LBJ asked, “Have we got anybody that’s got a military mind that can give us some military plans for winning that war?” McNamara mentioned General Earle (Bus) Wheeler, who would be appointed chairman of the Joint Chiefs of Staff in July to replace Maxwell Taylor, who was being sent to South Vietnam to replace Henry Cabot Lodge as U.S. ambassador, all meant to shore up the “mess” in Saigon, as it was being called in any number of private conversations.

LBJ said that in Wheeler’s recent trip to Vietnam, “he came back with planes, that’s all he had in mind…”

McNamara replied: “Well, uh, yes we had more than that, but he emphasized planes…”

LBJ: “Let’s get more of something, my friend, because I’m going to have a heart attack if you don’t get me something. I’m just sitting here every day and, uh, and this war…I’m not doing much about fightin’ it and, uh, I’m not doing much about winnin’ it…Let’s get somebody that wants to do something besides drop a bomb, but go in and take these damn fellas and run them back where they belong…”

But when U.S, combat options were put forward, Johnson rejected them, and his advisers couldn’t put forward any coherent alternatives.

On May 22, in a commencement speech at the University of Michigan, Johnson framed his vision as a “Great Society” to “enrich and elevate our national life.” The goal – an affirmation of the highest aspirations of the Declaration of Independence – was to eradicate poverty, inequality, and injustice.

“But most of all,” Johnson said, as his rhetoric soared, “the Great Society is not a safe harbor, a resting place, a final objective, a finished work. It is a challenge constantly renewed, beckoning us toward a destiny where the meaning of our lives matches the marvelous products of our labor.”

It may well have been impossible to reconcile these two tracks. Facing the reality in Vietnam, as McNamara came to believe, would mean accepting JFK’s ingrained belief that unless the South Vietnamese could demonstrate their own capacity to prevail politically and militarily, the U.S. could not do it for them. Yet in 1964, stating this unequivocally was never going to happen.

The U.S. had departed, in McNamara’s words, from the “fundamental principles that Kennedy had premised our intervention on without recognizing ourselves that we departed from them.” And so the Johnson administration was inexorably overtaken by events and the continuing contention that withdrawal or neutralization – as President Charles de Gaulle of France was advocating – would be considered unacceptable defeat.

When the decision was made to replace Lodge in Saigon, McNamara volunteered for the job. Johnson did not consider this, but at one point, the president asked McNamara if he would agree to serve as vice president on the 1964 ticket. “Knowing President Johnson as I did,” McNamara writes, “I knew that if I answered yes, he might later reconsider and withdraw the invitation. In any event, I said no.”

Over the summer, Johnson said he wanted McNamara to be his “number one executive vice president in charge of the Cabinet” in the next term.

In words private and public, LBJ and McNamara were to be inextricable going forward in how the war would be perceived.

*************************

In the decade of America’s Vietnam war, there were pivotal events that forecast the outcome. The November 1963 coup against Diem and Nhu and the political chaos that followed was certainly one such event. The Tonkin Gulf incidents of August 1964 were another. While minimal in actual warfare they became the baseline for what would transpire thereafter.

The details of the Tonkin Gulf incidents of late July and early August 1964 are straightforward enough. A covert South Vietnamese operation codenamed Plan 34A involved the infiltration of South Vietnamese agents with radios into the north and the use of hit-and-run attacks on North Vietnamese shore and island installations – in other words, a minor but direct assault on the North. The CIA supported these operations, and the U.S. military kept track of them.

The U.S. deployed patrols in the region (known as DESOTO patrols) as part of a global reconnaissance operation using specially equipped naval vessels to collect information that might be useful in any military confrontation with adversaries. Plan 34A and DESOTO were entirely separate. McNamara writes, “Most of the South Vietnamese agents sent into North Vietnam were either captured or killed, and the seaborne attacks amounted to little more than pinpricks…The South Vietnamese government saw them as a relatively low-cost means of harassing North Vietnam.”

On August 2, the two operations intersected when the U.S. destroyer Maddox, on DESOTO patrol, came into contact with North Vietnamese vessels firing torpedoes and automatic weapons – Hanoi’s retaliation for the Plan 34A activities a few days before. It was a summer weekend and, as he said, McNamara was in Newport visiting Jackie Kennedy. McGeorge Bundy was on Martha’s Vineyard doing what LBJ derisively described as “playing tennis at the female island.”

The U.S. had sanctioned Plan 34A, so the North Vietnamese assault on the Maddox was not really unprovoked.

“Well,” said Johnson, “it reminds me of the movies in Texas. You’re sitting next to a pretty girl, and you have your hand on her ankle, and nothing happens. And you move it up to her knee and nothing happens. And you move it up further and you’re thinking about moving a bit more and all of a sudden you get slapped. I think we got slapped.”

With that earthy quip, Johnson concluded that the episode was not a pretext for a military response – although it was later made clear that the attack on the Maddox had been ordered in Hanoi. A note of protest was sent to Hanoi asserting that the incident had been “unprovoked,” even though Plan 34A was in fact a provocation while DESOTO was technically not one.

On August 4, the Maddox returned to the Gulf of Tonkin accompanied by another U.S. destroyer, the USS Turner Joy. In Washington that morning, the Maddox reported that it was preparing for an imminent attack on a cloudy night with thunderstorms. The transcripts of radio traffic that night reveal (to keep a confusing point as simple as possible) and what history has concluded is that no actual attack on the U.S. ships ever took place, although they might have. Being unresolved, the consensus has become that the episode was a misrepresentation of the facts, which in the overall saga was considered deliberate deception rather than confusion.

What makes that judgment significant is that the Tonkin Gulf Resolution the administration put forward, which was passed unanimously by the House and 88-2 by the Senate on August 7, gave LBJ enormous power to pursue his objectives in Vietnam. It is also clear that no one anticipated that the authority approved after a minor incident in offshore waters would morph into a half-million American combat troops and a sustained bombing campaign that would go on for years.

Johnson’s political strategy for 1964 was vindicated by his sweeping victory over Barry Goldwater in the general election. He continued to stress moderation in his public statements and American “moral” purpose in helping the “weak defend their freedom.”

Yet whenever he gathered his military and political advisers, proposals went round and round without reaching tactical outcomes that could be implemented.

McNamara told his editors assessing what he wanted to say about that period:

“The Chiefs were much more divided than anybody understood and …there was a distinct failure – I don’t want to put it quite that bluntly, but there was a distinct failure of military leadership….

“There’s one place in here where I say, I failed…For fifty years, I’ve been a manager. For fifty years I dealt with organization. I know how to probe and penetrate and not accept things that are presented to me. I didn’t do it here. It’s my failure.”

So, at the end of Lyndon Johnson’s first year as president, with the mandate of leadership that he wanted so badly, the men who surrounded him were divided among themselves, whether always deliberately or not, misleading the public, exaggerating the prospect of Soviet or Chinese direct intervention in the war and about to launch the escalation that – they understood – was almost certainly hopeless.

Next Week: Part Nine: Fork in the Road

Lyndon Johnson’s decision to abandon the 1968 presidential election was the closest historical precedent for President Biden’s withdrawal. A remarkably, candid audio of McNamara discussing what led to the withdrawal with his editors in 1994 is at www.platformbooks.net.

And this piece, a guide to events of the moment.

To read previous installments in this series go to www.platformbooksllc.net. There is an archive of earlier pieces and a link to sources, acknowledgements and the audio of McNamara working with his editors on his memoir.

The C-SPAN interview on “LBJ-McNamara-Partnership Destined to Fail” has been postponed until orginal programming resumes at that hour in September.

Over the course of 1964 and 1965, most of the Kennedy senior team left the administration. McGeorge Bundy gradually found dealing with Johnson too hard. Ted Sorensen, the exceptional wordsmith, could not overcome his grief over Kennedy’s death. Press secretary Pierre Salinger, resident historian Arthur Schlesinger Jr., the political team from Boston all moved on, to be replaced by LBJ’s choices — Jack Valenti, Walter Jenkins, and Bill Moyers, among others.

There were changes as well among the Joint Chiefs, and Ambassador Henry Cabot Lodge in Saigon was replaced by General Maxwell Taylor. However, one leading official, Dean Rusk, stayed on, serving until the end of Johnson’s term in 1969 – and that may have been an underestimated aspect of all that was to go wrong.

With his editors, Robert McNamara explained his view of how government worked and how that contributed to what he considered an awkward “dynamic” in the administration:

“I think the American public and cabinet officers and residents don’t understand the government. They don’t understand there’s only one – leave out the vice president – there’s only one elected official in the Executive Branch. Every other person in the Executive Branch is appointed by the president…They have no independent power base…

“I didn’t believe I had independent power. This is one of the things that affected the way I behaved as secretary, particularly during Vietnam.”

McNamara’s definition of his role was never under any circumstances to undermine the people’s choice for the nation’s highest office – yet another reason that he subsumed his views on the war into Johnson’s quest for a validating election victory in 1964 and beyond. As secretary of defense and within his own limitations, McNamara carried out his role effectively.

That was clearly not the case with Secretary of State Dean Rusk. Though McNamara was adamant that he would not criticize Rusk personally in his book, nonetheless the portrayal of Rusk that emerges is negative. (Rusk died in 1994 before the book was published and while the writing was underway.) McNamara writes, “It was not a secret that President Kennedy was deeply dissatisfied with Dean Rusk’s administration of the State Department” but did not make a change, nor did Johnson.

In October 1964, Undersecretary of State George Ball, who was singular in his opposition to the Johnson administration’s Vietnam policy, sent a sixty-two-page memorandum which McNamara describes as remarkable for its “depth, breadth, and iconoclasm.” The memo was sent to Rusk, Bundy, and McNamara but did not reach Johnson, although in 1964 it probably wouldn’t have made a difference.

With his editors, and reflecting his appraisal of Rusk as ineffectual, McNamara asked rhetorically, “Where the hell was Dean? Here’s this guy who’s [under]secretary of state, saying we ought to get out and the goddamned memo didn’t even get to the president. And the view wasn’t raised. What in the hell was he doing running the State Department like that?

McNamara said that while he disagreed with Ball’s arguments, “I would have forwarded the memo to the President and said, ‘This is what…my deputy and he’s totally wrong and here’s why. But I want you to know that view exists.’ And we would have debated it…

“Now, that was Dean. And I’ve got to say this in a way that brings out the truth about Dean and yet doesn’t shaft him…Dean should have brought it to the president. And by God, if he didn’t …I should have.”

McNamara thought the Ball memo was important enough to return to it repeatedly as work on the memoir progressed. Ball’s opposition to the strategies put forward for Vietnam was the only serious high-level argument made against greater involvement. As the escalation decisions were discussed in 1965, Ball was again outspoken in opposition.

Rusk’s tenure was a reflection of Washington culture in the 1960s, which was still in the early stages of the use of leaks, asides, and rumors to demean White House staff and cabinet members. Even so, Rusk considered himself vulnerable.

McNamara was so astonished by one episode in the summer of 1967 that he included it in the book despite its personal nature:

“Dean phoned me one hot afternoon to ask if he could come to my office. I told him the secretary of state does not come to the secretary of defense’s office; it is the other way around. ‘No, no,’ he said, ‘it’s a personal matter.’ I said I did not care whether it was personal or official business – I would be in his office in fifteen minutes.

“When I arrived, he pulled a bottle of whiskey out of his desk drawer, poured a drink for himself, and said, ‘I must resign.’

“ ‘You’re insane,’ I said. ‘What are you talking about?’

“He said his daughter planned to marry a black classmate at Stanford University, and he could not impose such a political burden on the president…He believed that because he was a southerner, working for a southern president, such a marriage – if he did not resign or stop it – would bring down immense criticism on both him and the president.

“When I asked him if he had talked to the president, he said no, he did not wish to burden him.

“ ‘Burden him hell!’ I said. ‘You’ll really burden him if you resign. And I know he won’t permit it. If you won’t talk to the president, I will.’ ”

Johnson’s reaction was to congratulate Rusk on the marriage. The incident showed Rusk’s personal awkwardness, which doubtless was one of the reasons his influence on Vietnam was so vexed. As McNamara told his editors, “By the closing years of the administration, Rusk lived on whiskey and aspirin.”

In 1966, when George Ball left the State Department, Attorney General Nicholas Katzenbach accepted a demotion to become undersecretary of state, which was recognition that the department needed better management than Rusk could provide.

At the end of the Johnson years, McNamara told his editors, while he was at the World Bank and McGeorge Bundy was at the Ford Foundation, Rusk could not find a job. “Why did [Rusk] go to the University of Georgia? Hell…because he couldn’t get accepted anywhere else.”

For all that, McNamara considered Rusk “a great American,” an especially vivid example of one of the men who served Kennedy and then Johnson to his maximum capacity and nonetheless ended with a reputation in tatters and a career culminating in failure.

Rusk and McNamara led the departments with the operational responsibility for Vietnam. McGeorge Bundy as national security adviser was the third top-tier official, but without the administrative burden of a cabinet member. Bundy filled his role in every respect but one, and that was defining – his failure to help LBJ avoid the Vietnam abyss. Bundy’s role at Harvard, his pedigree and presence made him ideal for the Kennedy team, and his standing with LBJ as a man with the coolest of trappings who showed respect for Johnson worked well for about two years.

McNamara reveals in In Retrospect that after JFK’s death he was told by Bobby that the president had intended to replace Rusk in a second term with him. “I would have urged him to appoint Mac Bundy, whose knowledge of history, international relations, and geopolitics was far greater than mine,” he writes.

Although McNamara and Bundy’s policy role in the escalation were comparable, historians and pundits have not portrayed Bundy with the degree of animus that McNamara has received. That was, in my view, because of Bundy’s generally lighter touch in all dealings with others in the administration and the media. His long tenure as president of the Ford Foundation was recognized as a paragon of progressive philanthropy.

McNamara’s years at the World Bank were disparaged as an effort at redemption.

Gordon Goldstein, the author of Lessons in Disaster, says that Bundy’s never-completed memoir would have been as full of rueful explanations as In Retrospect. Bundy seemed to understand that he had been spared ignominy. The Bundy manuscript, such as it was, may someday be released and will make that clear.

Next Week: Part Eight: Politics and Provocation.

Lyndon Johnson’s decision to withdraw from the 1968 presidential election is being portrayed as a possible precedent for President Biden’s current campaign crisis and calls for him to leave the race. A remarkably, candid audio of McNamara discussing what led to the withdrawal with his editors in 1994 is at www.platformbooks.net.

Coming: July 28 on C-Span 1 Q-A 8 pm EDT/11 pm EDT/8 pm PT. Peter Osnos dicusses “LBJ-McNamara: The Vietnam Partnership Destined to Fail” with host Peter Slen for a full hour with audio and video of McNamara. It will be posted to C-SPAN’s website thereafter.

To read previous installments in this series go to www.platformbooksllc.net. There is an archive of earlier pieces and a link to sources, acknowledgements and the audio of McNamara working with his editors on his memoir.

The first days of Lyndon Johnson’s presidency were a mass of confusion, grief, abrupt realignments in position and prospects, and an immediate cascade of urgent issues and decisions that had to be made.

The LBJ tapes of those days show a president managing what were immediate challenges, including the creation of what became the Warren Commission after Chief Justice Earl Warren was persuaded to investigate the assassination and deal with conspiracy theories that to this day have never been completely resolved. What to say in his first address to a joint session of Congress was, not surprisingly, extremely sensitive, and Johnson relied on Ted Sorensen, Kennedy’s speechwriter, to get it right. And congressional action on the budget and taxes were a fixation for Johnson, who was doubtless relieved to be back in areas where he had experience rather than having to deal with the unprecedented aftermath of martyrdom of a young president.

A great deal has been written about Johnson’s relationship with the Kennedy family, especially Jackie and Bobby as they were always called, including by Johnson. Every conversation with the new widow in those days, and thereafter, was loving to the point of unctuousness, and she would respond with what sounded like purring. Altogether different was LBJ’s loathing of the attorney general and Bobby’s similar contempt for Johnson.

Johnson considered Bobby a political rival of major potential. For his part, Bobby, who so disliked LBJ he had tried to keep him off the 1960 ticket, considered the new president a usurper. The antagonism was beyond mediation.

William Manchester’s book The Death of a President captures every iota of real and perceived slights in the early weeks of the transition. Johnson’s combination of awe, envy, and suspicion of the Kennedys was a profoundly personal matter embedded in his character.

In time, the evolution of Bobby as heir to his brother’s political mantle and Jackie, who became, privately, a passionate opponent of the Vietnam war, would be strands in the unraveling of Johnson’s own judgment about the conflict. Because of Robert McNamara’s closeness to the family, this was an aspect of his dealings with LBJ that was especially hard to parse.

McNamara was an unusually loyal person and in that, he was sincere – in this case to three people whose relationships defied explicable boundaries.

For example, in August 1964, at the start of what became known as the Tonkin Gulf incidents – a major turning point in the direct battle with North Vietnam – a critical meeting took place in the White House on the morning of August 2. McNamara told his editors that the record of the sessions reveals that he was not in attendance, only arriving later in the day.

“Where the hell was I? I was at Newport with Jackie. She was at her mother’s house, had stayed overnight. Marg was traveling and I went up and stayed overnight Saturday night with Jackie.”

The point of the anecdote was that McNamara did not consider himself responsible, at least initially, for decisions about the Tonkin Gulf episode. In 1993, with Jackie alive at the time, he said, “I was and am close to Jackie. I’m very fond of her.” This explanation for his absence from the meeting was omitted in his memoir.

Vietnam was very much on the crowded agenda in late 1963 and 1964, and Johnson held multiple meetings with the national security leadership, reflecting the reality that the situation in the country after the ouster of Diem and Nhu had only gotten worse.

Johnson decided to send McNamara to Vietnam again to assess the situation. Upon his return to Washington on December 21, 1963, McNamara publicly said, as quoted in In Retrospect with words he added to the statement: “‘We observed the results of a very substantial increase in Vietcong activity’ (true); but I then added, ‘We reviewed the plans of the South Vietnamese and we have every reason to believe they will be successful’ (an overstatement at best).”

He continues, “I was far more forthright — and gloomy — in my report to the president. ‘The situation is very disturbing,’ I told him, predicting that ‘current trends, unless reversed in the next 2-3 months, will lead to neutralization at best or more likely to a Communist-controlled state.’”

In the memoir, McNamara raises, without answering, the question that was central to the reputation he developed for dissembling in his public appraisals of the war: “It is a profound, enduring, and universal ethical and moral dilemma: how, in times of war and crisis, can senior government officials be completely frank to their own people without giving aid and comfort to the enemy?”

And there is the essence of what would bedevil the Johnson administration going forward; consistently misleading the American public was a blunder with consequences then and to this day, well into the twenty-first century.

Vietnam and every other foreign policy issue at the height of the Cold War were subordinate, however, to Johnson’s singular priority: winning the presidential election in November 1964. If elected in his own right, he could stop deriding himself as the “accidental president.”

McNamara sparred with his editors over whether Johnson put off decisions on Vietnam solely for political reasons. The underlying problem, he insisted, was that there was no consensus among the military or among the president’s advisers on what should be done. The solution was to adopt wording like “Hard as it may be to believe…LBJ was not just making a political choice.”

Nothing in LBJ’s character, especially after the humiliation of the years as vice president, could possibly be more important to him than restoring his self-confidence as a politician and as a man with power and the capacity to use it.

The events of 1964 would be many, but the record shows that nothing would be allowed to diminish Johnson’s public stance in opposition to widening the Vietnam war, especially after the Republican Party nominated Barry Goldwater, who was fierce in his assertions that the administration was effectively conceding the war to the communists.

A fragment in Robert Caro’s The Passage of Power captures Johnson’s determination to keep Vietnam simmering. In March 1964, McGeorge Bundy, with some exasperation, asked Johnson, “What is your own internal thinking on this, Mr. President?”

Johnson replied: “I just can’t believe that we can’t take 15,000 [sic] advisers and 200,000 people [South Vietnamese troops] and maintain the status quo for six months. I just believe we can do that, if we do it right.”

Bundy’s biographer Gordon Goldstein writes in Lessons in Disaster that there was a “litany of nondecisions” in 1964 – “the decision not to withdraw, not to escalate, not to neutralize, not to debate the domino theory, and, fatefully, not to examine the military limitations and implications of a massive deployment of U.S ground combat forces to South Vietnam.” In Bundy’s mind, Goldstein concludes, politics became “the enemy of strategy” and the justification for official indecision and public deception.

McNamara’s position was unique among the senior advisers as the Johnson administration settled in. As a recognized family intimate of the Kennedys, he had to straddle his emotions about that and Johnson’s feelings about Jackie and Bobby while adapting his continuing role as secretary of defense to a vastly different person in the Oval Office.

McNamara writes in In Retrospect:

“Between his ascendency to the presidency and my departure from the Pentagon, President Johnson and I developed the strongest possible bonds of mutual respect and affection. However, our relationship was different from the one I had with President Kennedy, and more complicated. Johnson was a rough individual, rough on his friends as well as his enemies. He took every person’s measure. He sought to find a person’s weakness, and once he found it, he tried to play on it. He could be a bully, though he was never that way with me. He learned that I would deal straight with him, telling him what I believed rather than I thought he wanted to hear, but also that once he, as the president, made a decision, I would do all in my power to carry it out.”

In our transcripts, however, McNamara portrayed aspects of the relationship in another way. With the buildup in Vietnam underway in 1965, McNamara recommended a tax increase to pay the cost. “I said to Johnson, in effect, ‘That’s going to be inflationary, we have to have a tax increase.’ And Johnson said, ‘Where’s your vote count?’ I said, ‘…get your own damn vote count.’ He said, ‘You get your ass up there and get your vote count.’

“So, I make an effort and I get the vote count and I come back…Sure, I knew when I recommended it would be difficult. But I said I would rather try and fail than not at all. It’s the right thing to do.”

LBJ responded: “That’s what’s wrong with you, Bob, you don’t know a goddamned thing about politics.”

Bullseye. McNamara’s technocratic acuity and demonstrated willingness to carry out presidential edicts, was not matched by political judgment and measured public style. The result was his reputation for bombastic recitation of the facts, which he privately understood was a presentation flaw but could not modify.

Nuance in managing public perception was a Kennedy skill, and political savvy was Johnson’s. McNamara had neither.

Next Week: Part Seven: The State Department

To read previous installments in this series go to www.platformbooksllc.net. There is an archive of earlier pieces and a link to sources, acknowledgements and the audio of McNamara working with his editors on his memoir.

Secretary of Defense Robert McNamara was in a Pentagon budget meeting with senior military and civilian leaders about the upcoming budget and congressional debates at 2 P.M. on Friday, November 22, 1963.

McNamara’s intention was to go to Hyannis Port a few days later, to brief President Kennedy on the results after the president returned from his trip to Texas.

“In the midst of a discussion,” McNamara wrote in a draft chapter for his memoir In Retrospect, “my secretary reported a personal phone call….”in which he learned from Attorney General Robert Kennedy that the president had been shot.

In the transcripts of a recorded session in 1993 with his editors for his book In Retrospect, this exchange followed:

Editor: How could you have gone on with your meeting?

McNamara: Well – well, in the first place he wasn’t killed — the first point. Well, I stopped the meeting the moment I got the second call he was dead.

Editor: Yes, but even…..

McNamara: But in the first one…

Editor: The president had been shot. You were the secretary of defense. How come you didn’t go instantly…I mean, what if this was the beginning of an international coup?…

McNamara: Well, it didn’t appear that way. In any case, the simple fact is that I didn’t, the meeting did continue…

Editor: But maybe you were in shock?

McNamara: No, no, definitely not that. Now what it was, we didn’t think that it was serious, or we didn’t think there was anything we could do about it other than go ahead with the meeting…

In the book, after some consideration, McNamara wrote this about the meeting and the aftermath:

“My secretary informed me of an urgent, personal telephone call. I left the conference room and took it alone in my office. It was Bobby Kennedy, even more lonely and distant than usual. He told me simply and quietly that the president had been shot.

“I was stunned. Slowly, I walked back to the conference room and, barely controlling my voice, reported the news to the group. Strange as it may sound, we did not disperse: we were in such shock that we simply did not know what to do. So, as best we could, we resumed our deliberations.

“A second call from Bobby came about forty-five minutes later. The president was dead. Our meeting was immediately adjourned amid tears and stunned silence.”

McNamara gathered the Joint Chiefs of Staff and ordered U.S. military forces worldwide to be placed on alert. When the attorney general called again, it was to ask McNamara and Maxwell Taylor, the president’s top military adviser, to accompany him to Andrews Air Force Base to meet the returning casket.

“Shortly after we arrived at Andrews, the blue and white presidential jet slowly taxied up to the terminal, its landing lights still on. Bobby turned and asked me to board the plane with him. It so clearly seemed a moment of intimacy and privacy for a family in sorrow that I refused.…

“The Kennedys and I had started as strangers but had grown very close. Unlike many subsequent administrations, they drew in some of their associates, transforming them from colleagues to friends. We could laugh with one another. And we could cry with one another. It had been that way with me, and that made the president’s death even more devastating.”

Bobby now called to say that Jackie Kennedy wanted McNamara to join her at Bethesda Naval Hospital while she awaited the outcome of the autopsy.

“I drove immediately to the hospital and sat with Jackie, Bobby, and other family members and friends. In the early morning hours, we accompanied the president’s body back to the White House, where the casket was placed in the elegant East Room, draped by the flag he had served and loved and lit softly by candles.”

In the transcript, the closeness of McNamara to the Kennedys, and especially to Bobby, is especially vivid.

Editor: Under those circumstances would you be the person that they would turn to?

McNamara: Well, among the cabinet…But you see [Bobby] called me to go out [to Andrews] with him. And then, after we got there, he wanted me to board the plane. It was a very poignant moment. Here’s Johnson [also on Air Force One after being sworn in], and he didn’t give a damn about Johnson. I wasn’t there because of Johnson. Bobby just wanted me to go up with him, up the stairs and meet Jackie…

Editor: I mean Dean Rusk wasn’t there…

McNamara: Oh, hell no.

Editor: Mac Bundy wasn’t there.

McNamara: No, no.

Editor: So that, in today’s jargon, it would be correct to say that you had bonded…

McNamara: Oh, absolutely. No question about it…We bonded because we had shared values, number one, and [with Bobby] a shared sense of loyalty to the president. Bobby knew that I was loyal to the president. And he also, in a sense, knew that I was loyal to him.

****************************

November 22, 1963, was the day that everything changed.

William Manchester’s intricately detailed account of that day, The Death of a President, provides names, places, and reactions to the news as word spread of John F. Kennedy’s assassination. Most people, wrote Manchester, simply could not believe what had happened, even after his death was confirmed at Parkland Hospital in Dallas.

The tenor of the country was suddenly transformed. The indelible images of that weekend were of the widow and children attending the burial at Arlington; John Jr. saluting his father’s casket; and Lee Harvey Oswald being shot to death in a Dallas police station by Jack Ruby. Those moments were especially powerful because they were shown live on television. Tens of millions of Americans shared the drama and for all, very young to very old, they were never to be forgotten. Quite literally for the first time, every American could be present at the same historical moments.

Something else was happening that weekend. The presidency was being transferred from the New Frontier of John F. Kennedy and his cohort to Lyndon Johnson, who as an American political figure was from an entirely different culture, not by generation but in every other way. As a personality, Kennedy was elegant and cool. Johnson was intense and physically awesome. He came from the hardscrabble Texas hinterland, and his political trajectory was rough and tumble, whereas Kennedy’s was, at least as seen by the public at that time, smooth.

When LBJ ascended to majority leader of the Democrats in the U.S. Senate, he was brilliant in the handling of power; his biographer Robert Caro’s volume on those years is titled Master of the Senate. In 1960, his bid for his party’s presidential nomination was clumsy and ended at the Democratic National Convention, where in a fraught process leaving bruises on all involved he was named to the ticket as vice president, ostensibly to make Kennedy more palatable to southern states.

Biographers’ accounts of Johnson as vice president describe a time of indignity and mishap. Kennedy himself did not turn on Johnson but used him sparingly on any matters of consequence. Bobby Kennedy, on the other hand, pursued a personal animus for LBJ, and the overall sense in Washington was that Johnson had been humiliated.

After Kennedy’s day in Dallas, he had been scheduled to fly to the LBJ Ranch for an evening with Johnson and Lady Bird. All the preparations for the presidential stopover were complete.

As the historian Max Holland writes in the introduction to his book Presidential Recordings: Lyndon B. Johnson:

“Lyndon Johnson rarely got to spend an extended amount of time with the President under such casual circumstances and intended to use the occasion to discuss his most pressing concern: his place on the November 3 ballot, less than a year away. Within political circles and the media, rumors abounded that Johnson would be unceremoniously dumped from the Democratic ticket…

“The Vice President’s pride was deeply wounded, for he had taken great pains to be loyal to the administration and did not deserve to be treated this way. Such rumors did not arise on their own in Washington; someone credible in the administration had to be generating speculation or doing something. Consequently, the Vice President intended to use the evening of November 22 to deliver a stunning message of his own.

“Lyndon Johnson did not want to be on the Democratic ticket in 1964.”

This revelation also appears in Kenneth W. Thompson’s book, The Johnson Presidency: Twenty Intimate Perspectives of Lyndon B. Johnson. Another version has Johnson stepping down to become president of his alma mater, the Southwest Texas State Teachers College in San Marcos.

Whatever the case may have been, by the evening of November 22, 1963, the world had changed. Lyndon Johnson was now the president of the United States and had flown to Washington to assume the office and its responsibilities.

Next Week: Part Six: The Accidental President

To read previous installments in this series go to www.platformbooksllc.net. There is an archive of earlier pieces and a link to sources, acknowledgements and the audio of McNamara working with his editors on his memoir.

The account provided by Robert McNamara and many other participants and writers about the Cuban Missile Crisis in October 1962 shows how President John F. Kennedy was surrounded by senior officials and advisers recommending military intervention in Cuba to force the Soviets to remove the weapons it had placed there. Instead, he chose to use a naval blockade and some secret bargaining over U.S. missiles in Turkey to end the confrontation.

On the evening of October 15, National Security Adviser McGeorge Bundy was hosting a dinner party that was interrupted by a call from Ray Cline, the deputy director of the CIA, who said that reconnaissance photography had confirmed that the Soviet Union was deploying medium-range nuclear missiles in Cuba.

Bundy returned to the dinner party without informing the president.

He later explained to Kennedy, “I decided that a quiet evening and a night of sleep were the best preparation you could have in light of what would face you in the next days.”

At eight o’clock the next morning, with Kennedy still in his pajamas, sitting in bed reading the newspapers, Bundy informed him of the crisis.

Over the next thirteen days, Kennedy convened multiple sessions of advisers, designed the Executive Committee of the National Security Council, or “ExComm,” to consider options for having the missiles removed. Among this group were the Soviet experts Charles (Chip) Bohlen, George F. Kennan, and Llewellyn Thompson, whose collective experience with the Kremlin provided a level of insight that was especially valuable.

To highlight the intensity of the moment, McNamara told us in our editorial sessions that he never went home during the entire period. He slept at the Pentagon for the next twelve nights.

“It wasn’t that I felt the military wouldn’t pursue the instructions we laid down, not at all…It was that this was a very delicate communications problem between Kennedy and Khrushchev, and we didn’t want a war and we wanted to get the goddamned missiles. How do you get the missiles out without a war? We put in the quarantine.”

The deliberations that led to the outcome have been dissected and analyzed in any number of books and studies.

In Retrospect has this account:

“By Saturday, October 27, 1962 – the height of the crisis – the majority of the president’s military and civilian advisers were prepared to recommend that if Khrushchev did not remove the Soviet missiles from Cuba (which he agreed to the following day) the United States should attack the island. But Kennedy repeatedly made the point that Saturday – both in Executive Committee sessions and later, in a small meeting with Bobby, Dean, Mac, and me — that the United States must make every effort to avoid the risk of an unpredictable war. He appeared willing, if necessary, to trade the obsolete American Jupiter missiles in Turkey for the Soviet missiles in Cuba in order to avert the risk. He knew such an action was strongly opposed by the Turks, by NATO, and by most senior U.S. State and Defense Department officials. But he was prepared to take that stand to keep us out of war.”

Ultimately, the crisis ended with the blockade and secret agreement about the missiles in Turkey but remains the closest that the United States came to a confrontation with the Soviet Union over nuclear weapons. McNamara’s view of the episode was framed around Kennedy’s rejection of the advice of his Joint Chiefs to use force in Cuba. In our discussion, he said:

“Had we invaded that island, as a majority of Kennedy’s military and civilian advisers were recommending…and they were recommending it be done three or four days later – attack and later invasion – those damn warheads would have been used, without any question.”

Kennedy’s position was:

“He didn’t believe that a president and I didn’t believe a secretary of defense should expose our nation to even a small risk of a catastrophe. That’s why I don’t think he would have moved in Cuba.”

As 1963 unfolded, the Saigon government of Ngo Dinh Diem and his brother Ngo Dinh Nhu had become increasingly fierce in its crackdown on the Buddhists who were critical of the Catholic-led regime. Diem held the leadership position with Nhu at his shoulder. The view in Washington was, as it so often was in similar circumstances, “He’s a son of a bitch, but he’s our son of a bitch.” The view had been to do everything possible to support Diem. On June 11, Thich Quang Duc, a revered elder among the Buddhist monks, immolated himself in protest of the repression of the Buddhists, which Malcolm Browne of the Associated Press captured in a photograph that symbolized the scale of what was happening.

Restraining repression became a focal point of U.S. policy, along with a growing awareness of the successes in the countryside of the communist Vietcong guerrillas. How much pressure could be applied on Diem and Nhu? And there was a sense that some generals in the Armed Forces of the Republic of Vietnam (ARVN) were moving toward a coup. The U.S. ambassador in Saigon, Frederick Nolting, got along well with Diem, but his deputy, Bill Truehart, took a much harder line with the South Vietnamese president when Nolting left Vietnam for six weeks at a moment of serious tension. Truehart had sided with those who wanted to oust Diem. Nolting wanted to continue working with him. According to his son Charles Truehart’s book Diplomats at War: Friendship and Betrayal on the Brink of the Vietnam Conflict, Nolting on his return was furious.

In Washington, officials increasingly shared the sense that Diem and Nhu were unwilling and unable to change their attitudes and actions. The more the crackdown against Buddhists went forward – and the less it seemed that U.S. influence was working, it became clear that something had to be done.

By now it was high summer, and the principal decision makers were away from Washington. Kennedy was in Hyannis Port. McNamara and Marg were in the Grand Tetons. Bundy, Secretary of State Dean Rusk, and CIA Director John McCone were all away as well.

On August 24, McNamara writes, “several of the officials we left behind saw an opportunity to move against the Diem regime. Before the day was out, the United States had set in motion a military coup, which I believe was one of the truly pivotal decisions concerning Vietnam made during the Kennedy and Johnson administrations.”

McNamara identifies Roger Hilsman, the assistant secretary of state for Far Eastern affairs, as the prime mover of this effort: “Hilsman was a smart, abrasive, talkative West Point graduate…He and his associates believed we could not win with Diem and, therefore Diem should be removed.” Hilsman then drafted a cable to Henry Cabot Lodge Jr., who had just arrived in Saigon to replace Nolting as the new ambassador. The cable said:

“It is now clear that whether the military proposed martial law or whether Nhu tricked them into it, Nhu took advantage of its imposition to smash pagodas…Also clear that Nhu has maneuvered himself into commanding position.

“U.S. Government cannot tolerate situation in which power lies in Nhu’s hands. Diem must be given chance to rid himself of Nhu and his coterie and replace them with best military and political personalities available.

“If, in spite of all your efforts, Diem remains obdurate and refuses, then we must face the possibility that Diem himself cannot be preserved.”

As the draft cable ricocheted through the vacationing officials it was finally sent to Kennedy with assurances that it had been approved by the senior cabinet members, but because of the dispersal of the participants, this was more than had actually happened. Reluctantly, Kennedy said it was okay to transmit.

Only then was the cable shared with General Maxwell Taylor, the president’s military adviser, a World War II hero “and the wisest uniformed geopolitician and security adviser I ever met” according to McNamara. Taylor had been appointed to that role because Kennedy knew that the Joint Chiefs of Staff as a group had been wrong in the Bay of Pigs and in the missile crisis, and while he trusted McNamara and Bundy, he did not trust the generals.

Taylor was shocked that the cable had already been sent. He called what the anti-Diem faction in Washington had done “an egregious end run” while high-ranking officials were away.

Cables and memoranda were the primary means of group communications in Washington and with Saigon. In meetings, differing views were shared and heard by all. But written communications increased the risks of misunderstanding – who wrote them, who received them and who did not, who read them and who did not. In our internet age, we encounter the same sort of problem — think of a mistyped “reply all,” for example. The possibility that Diem could be removed was now in bureaucratic play. And the record indicates that Kennedy was equivocal in how own judgment on the situation – to his later chagrin.

There is no doubt that in the months of September and October the possibility of a military coup increased. But what happened on November 1 was not anticipated, at least by Kennedy. After Diem and Nhu had agreed to surrender, they were placed in an armored personnel carrier and murdered, with grisly photos of their bodies published worldwide.

Kennedy was appalled.

On Monday, November 4, he dictated this memo: “Over the weekend, the coup in Saigon took place, culminated three months of conversations about a coup, conversations which divided the government here and in Saigon. Opposed to a coup was General Taylor, the attorney general, Secretary McNamara….In favor of the coup was State, led by Averell Harriman, George Ball, Roger Hilsman….I feel that we must bear a good deal of responsibility for it beginning with our cable of early August in which we suggested the coup. In my judgment that wire was badly drafted, it should never have been sent on a Saturday.”

(Kennedy did not mention Secretary of State Dean Rusk in this dictation, which over the years to come would show that Rusk never was as much of a confidant or influence on JFK and later Lyndon Johnson as might be expected of a secretary of state. But he stayed in office until the end of Johnson’s term.)

“I was shocked by the death of Diem and Nhu,” Kennedy said, adding that Diem “was an extraordinary character and while he became increasingly difficult in the last months, nevertheless over a ten-year period he held his country together to maintain its independence under very adverse conditions. The way he was killed made it particularly abhorrent. The question now, whether the generals can stay together and build a stable government…”

They could not.

And so, on November 22, 1963, the political situation in Saigon was a mess and despite some professed claims of progress around the country, the downward trajectory was continuing. Kennedy’s advisers were addled and squabbling over who did what to whom in fomenting the coup.

McNamara, in his book discussion with his editors, made the case – stronger than he would do elsewhere – that Kennedy would have proceeded with his planned withdrawal of U.S. forces in 1964 and 1965.

“He would have, particularly, I think, recognized that the conditions we had laid down, specifically that he had stated categorically a few days before – i.e., it was a South Vietnamese war; it could only be won by them; and to do that they needed a sound political base – were not being met.

“Therefore, whatever the costs of withdrawing – and, as I say, I think he would have thought they were greater than, with hindsight, we know them to have been — I say he would have accepted the domino theory back then…He would have accepted that cost, because he knew that the conditions necessary to avoid it weren’t there and couldn’t be met and in an attempt to meet them, we would spill our blood, and he wasn’t about to do that…”

This was also the conclusion of Clark Clifford, who knew Kennedy well and was later to be Johnson’s secretary of defense. In an interview with his editors for his memoir Counsel to the President, Clifford said that JFK was firmly set against deploying ground troops to Vietnam. “In judging matters of this kind [Kennedy] was a real cold fish,” Clifford said. “He could be totally objective…under the façade of charm and attractiveness…He was cold, calculating and penetrating.” Clifford said that he could imagine Kennedy concluding in so many words, “I’m not willing to take the chance. I don’t like what I see ahead. I’m suspicious of the people who are involved. I just don’t think I ought to accept the representations of the military with full faith and credit extended…I’m just going to get more deeply involved in what is a stinking mess.”

Nonetheless, the Kennedy presidency was unquestionably dominated by the belief – and reality – of Soviet and related communist threats in Europe and Asia. Kennedy’s responses to those reflected an instinct, shared on the whole with McNamara, to deflect confrontations rather than meet them directly with force. His terrible experience with the Bay of Pigs, events around the building of the Berlin Wall in 1961, the Geneva conference in 1962 which ended with the neutralization of Laos, and the Cuban missile crisis demonstrated a strategy to avoid catastrophic outcomes.

McNamara believed that Kennedy had concluded that the pretext for the continuing war in Vietnam – to head off Soviet influence and Chinese participation in Asia, as had happened in Korea a decade earlier, was not worth the cost it would entail. In ways expressed by the Soviet expert George F. Kennan and politicians like Senator Fulbright (and by McNamara in the 1990s), exaggerating Soviet power and the overall communist threat was, in many ways, as bad and certainly as perilous as underestimating it.

As for Vietnam, McNamara said years later, Kennedy and his advisers, for all their pizazz, were ignorant in almost every way possible about Southeast Asia its languages, history, and culture — and moreover, in a global battle with communism, Vietnam “was a tiny blip on the radar.” But because “we screwed up,” he said bluntly, the blip would eventually overwhelm so much else.

In discussing the Kennedy presidency, McNamara’s editors returned again and again to the matter of what Kennedy would have done in Vietnam had he lived. Most historians tend to believe that Kennedy would have had to reverse the withdrawal of U.S. advisers, but this was not what McNamara really believed.

Why would he make so firm a statement to the editors when he refused to make it publicly?

“I’m doing it here for only one reason. Because if I think as I do – that he would have gotten out, then it is incumbent upon me to explain why those of us who worked with him, including Johnson, didn’t get out…I don’t raise it because I’m not trying to…vindicate Kennedy or admire him or support him or whatever.

“I raise it only because the burden of proof is on those of us who stayed…why the hell…”

Kennedy had all the members of his cabinet and the National Security Council read Barbara Tuchman’s book The Guns of August about the origins of World War I. She reports one former German chancellor asking another, “How did it happen?”

The other replies, “I wish I knew.” In other words, they bungled into war.

“I don’t ever want to be in that position,” Kennedy said. “We are not going to bungle into war.”

Next Week: Part Five: When Everything Changed

To read previous installments in this series go to www.platformbooksllc.net. There is an archive of earlier pieces and a link to sources, acknowledgements and the audio of McNamara working with his editors on his memoir

The victory of the Kennedy-Johnson ticket in 1960 over Richard Nixon and Henry Cabot Lodge (who would later serve as the U.S. ambassador in South Vietnam for Kennedy) was by a narrow margin. The role played by Mayor Richard J. Daley of Chicago in securing a victory in Illinois that had sealed the win for John F. Kennedy was regarded with some suspicion – a reflection of the fact that when it came to political goals, the Kennedy family and their operatives knew hardball.

But as the appointments to the White House staff and the cabinet went forward leading up to the January inauguration, the choices were considered notable for their distinction and personal dignity. Dean Rusk, a former Rhodes Scholar who was president of the Rockefeller Foundation in New York, was named secretary of state. Douglas Dillon, a patrician investment banker, was the new secretary of the treasury, and McGeorge Bundy, who had been named Dean of the Faculty of Arts and Sciences at Harvard at age thirty-four, was to be the national security adviser.

Robert S. McNamara had been educated at the University of California at Berkeley and Harvard Business School, and had served under General Curtis LeMay as one of the men who planned bombing raids over Japan, which were in time responsible for hundreds of thousands of Japanese dead, the majority of whom were civilians.

In Errol Morris’s Oscar-winning documentary, The Fog of War, McNamara quoted LeMay as saying later, “If we’d lost the war, we’d all have been prosecuted as war criminals.” McNamara then observed, “And I think he’s right. He, and I’d say I, were behaving as war criminals. LeMay recognized that what he was doing would be thought immoral if his side had lost. But what makes it immoral if you lose and not immoral if you win?”

LeMay’s bombast was instinctive. As a bomb spotter in World War II, McNamara had been a technocrat.

In the immediate postwar years, any personal reflections of McNamara’s role in the war were doubtless submerged beneath the surface as he focused on his career and the family he started with his beloved wife, Marg. After his military service he had joined the Ford Motor Company as one of the “Whiz Kids,” with a mandate to modernize the automaker, rising to the position of president of the company in late October 1960. Then, on December 8, only weeks later, McNamara was approached by Sargent Shriver, JFK’s brother-in-law, who said he was authorized to offer him the position of secretary of defense.

“This is absurd!” McNamara replied. “I’m not qualified.”

Two people had recommended McNamara to the president-elect. John Kenneth Galbraith, the famed Harvard economics professor, and Robert Lovett, a senior figure in the group of former officials who came to be known as “The Wise Men” because of their stature and national security experience. Significantly, these men had all been shaped by their experiences in World War II and the Soviet-American power clash, with the potential of a nuclear war that in the 1950s was a permanent threat. Also, there had been a communist takeover in China, followed by the war in Korea, which had ended in stalemate.

When McNamara told Kennedy that he was not qualified by experience to be secretary of defense, Kennedy replied, “Who is?” There were no schools for defense secretaries, Kennedy observed, “and no schools for presidents either.”

For all his management success at Ford and reputation for effectiveness, McNamara had this private worry:

“What do I know about the application of force and what do I know about the strategy required to defend the West against what was a generally accepted threat…[and] the force structure necessary to effectively counter the threat?”

Personal doubt as a senior government official – a recognition of limitations — then or thereafter were not meant to be worthy of serious consideration in policy debates. Once named, a secretary of defense was assumed to be qualified.

When McNamara agreed to take the job, Kennedy immediately announced it, and the televised images were of these two vigorous men in their early forties, showing none of whatever qualms they may have had about the jobs they were assuming.

McNamara’s primary challenge, as it had been at Ford, was to oversee the management and operations of a vast infrastructure that needed to be modernized. To achieve this, McNamara had insisted as a condition of taking the job that Kennedy let him make all appointments on his own.

This led to a particular disagreement over the post of secretary of the navy. McNamara read an article in The New York Times that reported that Franklin D. Roosevelt Jr. was to be named to the post.

In our editorial session transcript, McNamara recalled:

McNamara: I didn’t pay attention. I didn’t realize that was [Kennedy’s] desire, and somebody leaked it and it was a done deal. I go along, couple of weeks, and I’m appointing people, and the president’s approving them all, and he says, “Bob, you are making wonderful progress, but you haven’t recommended anyone for secretary of the navy.”

I said, “Mr. President, I just can’t find the right person.”

“Well,” he said, “have you thought of Franklin Roosevelt?”

“Well,” I said, “Hell, he’s a drunken womanizer.”

And he said, “Well, have you met him?”

And I said, “No, I haven’t.”

“Well, he said, “don’t you think you ought to meet him before you make a decision?”

I said, “Sure, I’ll be happy to. Where in the hell is this guy?”

“Well, he’s a Fiat dealer.”

So, I got the Yellow Pages out, looked down. I found the Fiat place in Washington, got him there and I….

I don’t know that they ever met. Ultimately, Roosevelt was named undersecretary of commerce. McNamara’s choice for the navy position was John Connally of Texas, who had been LBJ’s campaign manager at the Democratic convention, which meant that Kennedy was well aware of him and might well have been suspicious of his loyalty. Connally got the job and served until he resigned to run for governor in 1962. (And in 1963, he was in Kennedy’s car on the day the president was killed. He was wounded himself and nearly died.) Connally later switched parties became a powerful figure in the Republican Party, and he ran, unsuccessfully, in 1980 for its presidential nomination.

McNamara: I was right on Franklin Roosevelt, and I was right on Connally. Connally was one of the loyalest people in town for Kennedy…[The president] knew he had made a deal with me. He knew he was going to lose a secretary of defense if he didn’t go along this way, and he would have…

And that’s one of the things that bonded us. You know, I loved the guy. But I had certain standards. I had certain requirements. He understood them and he knew God-damned well I was going to do them.

McNamara was using this episode as a way of framing his relationship with JFK, and the savvy management of political issues as they arose, working around the problem together rather than turning stubbornness into a damaging confrontation.

In The Fog of War, Errol Morris asked McNamara how far he would go in challenging presidential authority, the role he might have played as Vietnam moved to the center of LBJ’s years in office, and whether he might have held his ground when there were policy issues on which he and the president disagreed. This answer, repeated in various formats over the ensuing years, would be McNamara’s explanation: He was an appointed adviser to the person with the election mandate to decide.

“Morris: To what extent did you feel that you were the author of stuff, or that you were an instrument of things outside your control?

“McNamara: Well, I don’t think I felt either. I just felt that I was serving at the request of the president, who had been elected by the American people. And it was my responsibility to try to help him carry out the office as he believed was in the interest of our people.”

When it came to Vietnam, this was not a challenge for McNamara in dealing with Kennedy, as it was later to become with Lyndon Johnson. In October 1963, Kennedy and McNamara were making contingency plans to start withdrawing the 16,000 military advisers the U.S. then had in Vietnam. It was Kennedy’s strong opinion that the war was South Vietnam’s to fight and win – and should not be America’s responsibility.

Having just returned from a survey trip to Vietnam that fall, McNamara knew that the situation there – militarily across the country and in Saigon, where the political scene was increasingly chaotic and getting worse. That reality then and thereafter was what McNamara knew to be the case – but was not what he would say in his many public opportunities to do so.

And then Kennedy was assassinated. The signoff on an American withdrawal was tabled. What JFK would have done in 1964, 1965, and beyond will never be known.

**************************

The thousand days of the Kennedy presidency were, on the whole, a period in which the American domestic situation was, by historic standards, relatively stable. The civil rights confrontations in the South were increasing – as when Kennedy had to call out the National Guard to accompany James Meredith in 1962 as he sought to become the first Black student at the University of Mississippi.

Congressional action was stymied by the nature of the Democratic majority, which consisted of labor activists and liberals in the North and segregationists in the South, including some of the most powerful politicians of that era. The Republican Party was beginning its long-term evolution from Eastern establishment figures like Governor Nelson Rockefeller of New York to conservatives like Senator Barry Goldwater of Arizona, who was to become the party’s firebrand pro-war candidate for president in 1964.

In foreign policy, to the extent that there was a bipartisan position, it was based on developments in the Cold War with the Soviet Union. The question was not whether to accept the Soviets as a great power and recognize Mao Zedong’s Communist China, but how far to go in taking them on for global influence and power. In the McCarthy period of the early 1950s, anyone who could be tainted with a hint of subversive activity or thoughts was persecuted, blacklisted, or jailed — and that included leading State Department experts on China.

The Korean War, which had ended in a stalemate in 1953, had resulted in an unequivocal and potentially dangerous U.S. role on the peninsula. And in Europe, a divided Berlin was the proverbial flashpoint for war. When the Berlin Wall was erected in the summer of 1961, Soviet intentions were deemed hostile to the extreme. The possibility of an all-out nuclear exchange reached its apogee the following year, when Soviet missiles were placed in Cuba, putting much of the United States within range.

Two episodes in particular would shape Kennedy’s approach to dealing with Vietnam, which at the time seemed a distant and not especially urgent problem. An International Agreement on the Neutrality of Laos at the end of a sixteen-nation conference in Geneva in 1962 essentially removed one of the Indochina states from the center of Cold War disputes. Settling the Laos issue was in itself not terribly significant, but it did mean that under the right circumstances, a negotiated outcome to conflict in Asia was possible.

But more prominent in Kennedy’s mind was the Bay of Pigs debacle. In April 1961, a group of Cuban exiles with CIA backing and Pentagon support were demolished just days after their invasion of the island, with the goal of wresting it away from Fidel Castro’s revolutionary government. This was a searing early lesson in failure for JFK, though it received short narrative shrift in the early pages of McNamara’s memoirs and in our discussions.

The Eisenhower administration had authorized the CIA to organize a brigade of 1,400 Cuban exiles as an invasion force to overthrow Castro, who had seized power in 1959 and had since become an avowed supporter of Soviet-style communism. The new Kennedy administration had allowed preparations for the invasion to carry on. “For three months after President Kennedy’s inauguration,” McNamara writes in In Retrospect, “we felt as though we were on a roll. But only a few days after he presented the defense blueprint to Congress, we faced a decision that showed our judgment – and our luck — had severe limitations.”

Kennedy, McNamara writes, gathered about twenty of his advisers to a State Department meeting to make a final decision on whether to proceed. Only one person, Senator William Fulbright, dissented “vigorously.” The Joint Chiefs of Staff endorsed the plan, as did Secretary of State Dean Rusk and McGeorge Bundy. McNamara concurred as well, “although not enthusiastic.”

The invasion launched on April 17, 1961, and McNamara quotes a historian who called it “a perfect failure.” It ended in days, with the invaders killed, wounded, or captured. Watching JFK on national television taking “full responsibility” was a “bitter lesson” for McNamara:

“I had entered the Pentagon with a limited grasp of military affairs and even less grasp of covert operations. This lack of understanding, coupled with my preoccupation with other matters and my deference to the CIA on what I considered an agency operation, led me to accept the plan uncritically. I had listened to the briefings…I had even passed along to the president, without comment, an ambiguous assessment by the Joint Chiefs that the invasion would probably contribute to Castro’s overthrow even if it did not succeed right away. The truth is I did not understand the plan very well and did not know the facts. I had let myself become a passive bystander.”

When he met with Kennedy and offered to take his measure of the blame, the president said that this was unnecessary. “I did not have to do what of all you recommended,” Kennedy said. “I did it. I am responsible and I will not try to put part of the blame on you, or Eisenhower, or anyone else.”

McNamara adds: “I admired him for that, and the incident brought us closer. I made up my mind not to let him down again.”

McGeorge Bundy never completed his version of a memoir although he worked with the historian Gordon M. Goldstein in preparing one. Goldstein published his own book, Lessons in Disaster: McGeorge Bundy and the Path to War in Vietnam, based on their discussions and on those parts of the book Bundy had drafted before he died.

Lesson one for Bundy, Goldstein writes, grew out of the Bay of Pigs experience. That lesson was: “Counselors Advise but Presidents Decide.”

This straightforward summary explains why, after the Bay of Pigs and as American escalation in Vietnam grew through the Johnson years, the president sought advice but only he, LBJ, could make the final decisions. And Johnson’s decisions were always made with politics uppermost in his mind. Beneath the surface, and not visible to others, were his doubts and confusions about the choices he was making.

Next Week; Part Four: Early Decisions

Sources and Acknowledgements and the audio of McNamara wirking with his editors can be found at www.platformbooksllc.net

Lyndon Johnson and Robert McNamara knew the war in Vietnam could not be won—and waged it anyway

BY PETER OSNOS

Of all those considered responsible for the outcome of America’s Vietnam debacle, President Lyndon B. Johnson and Secretary of Defense Robert S. McNamara usually get the most blame.

It was they who turned a commitment of roughly 15,000 U.S. military advisers into a force of more than 500,000 combatants that proved unable to hold off the North Vietnamese Army and the Viet Cong, leaving behind a unified nation aligned with the global Communist bloc.

As a correspondent in Vietnam, Cambodia, and Laos for The Washington Post between 1970 and 1973, and as the editor and publisher of major memoirs and histories on the subject, I have been immersed in the events of that era for a half-century.

This experience is what is contained in LBJ and McNamara: The Vietnam Partnership Destined to Fail, a serial that is running over 18 weekly installments on Peter Osnos PLATFORM, my newsletter on Substack. This amounts to a book delivered in a digital-word format for storytelling, the way podcasts do with audio.

Among the works I edited, the most significant was Robert McNamara’s memoir, In Retrospect: The Tragedy and Lessons of Vietnam, which, when published in 1995, renewed the sense that he, Lyndon Johnson, and their administration waged a war that Americans came to believe was an immoral display of superpower hubris.

In the memoir, the former secretary of defense acknowledged as much. “We were wrong, terribly wrong,” McNamara wrote. “We owe it to future generations to explain why.… We made an error not of values and intentions but of judgment and capabilities,” a formulation he devised as we concluded two years of extensive work together on the narrative.

Even so, McNamara’s words fell short of an outright apology, and thus there was never a chance that he would be forgiven for what happened. But the book and, later, Errol Morris’s Oscar-winning documentary, The Fog of War, based on his filmed interviews with McNamara, established an account of the collective mistakes and misleading statements of progress that made, and continue to make, Americans so skeptical of what the U.S. government says and does in shaping foreign policy.

There were hundreds of pages of transcripts from my extensive editorial sessions in McNamara’s Washington office, where I was accompanied by my editorial colleague Geoff Shandler and McNamara’s historian collaborator, Brian VanDeMark. When I reviewed these transcripts and listened to the tapes from which they were created, I realized that they were illuminating beyond what appeared in the memoir.

“We were wrong, terribly wrong,” McNamara wrote. “We owe it to future generations to explain why.”

To help others understand that process, I have posted a two-hour edited version of the audio at platformbooksllc.net, in which the four of us, at times laboriously, find exactly the best possible description of events—including some details that were considered too personal for the book, regarding individuals who have since died.

I was also the editor of the memoirs of Clark Clifford, who was a formidable unofficial adviser to Johnson and McNamara’s successor at the Pentagon, and the memoirs of Anatoly Dobrynin, the Soviet ambassador in Washington, who provided the Kremlin’s view of the war.

Lady Bird Johnson’s White House diaries were especially striking about Lyndon Johnson’s growing awareness that he was in a war that could not be won in any conventional sense—and his resulting despair. Similarly revealing was the unfinished memoir of National-Security Adviser McGeorge Bundy, who left the administration in 1966 and was never vilified the way L.B.J. and McNamara would be.

Most important as a resource were Lyndon Johnson’s tapes—his copious recordings of himself in conversation, including with McNamara. Johnson’s tapes reflect how his surpassing ambitions and his legacy in domestic matters were undermined by Vietnam.

I also benefited from Robert Caro’s four-volume biography of Johnson, the fifth volume of which (currently in progress) will deal more deeply with Vietnam.

These resources, and with the work and support of VanDeMark, a professor at the U.S. Naval Academy, and Robert Brigham, a distinguished Vietnam historian at Vassar College, enabled me to present a portrait of L.B.J. and McNamara that shows—conclusively, because so much of it is in their own words—that from the day Johnson took over from the assassinated President John F. Kennedy, on November 22, 1963, until McNamara’s last day as secretary of defense, on February 29, 1968 (when he became so overcome with emotion at a White House ceremony that he could not speak), both men were aware that they faced a challenge in Vietnam that they could not meet.

But they went ahead, accepting the reassurances they received from generals, intelligence operatives, and diplomats that headway was being made—even when those pronouncements conflicted with the facts in the war zone itself.

The reality is that a great power cannot prevail in a conflict where the strategies are flawed. McNamara hoped that the lessons of In Retrospect might guide future administrations. All this happened in the 1960s, decades before the United States followed many of the same trajectories in its 21st-century wars in Iraq and Afghanistan.

LBJ and McNamara: The Vietnam Partnership Destined to Fail is available to read in chapters on the Platform Books Web site starting this mont

This series begins with the presidency of John F. Kennedy and continues year by year through the term of Lyndon B. Johnson.

Parts Three, Four, and Five cover 1961-63, the Kennedy years, during which the Cold War with the Soviet Union was at its height, but the tense and perilous face-offs in Berlin and Cuba did not lead to the conflagrations that were feared. The movement for civil rights featured nonviolent protest, conveying a sense of dignified determination to defy racism, even as those resistant to racial integration often employed violent means themselves.

Overall, the mood in the country seemed to be lifted by the dynamic, glamorous presence of Kennedy, his family, and his cohort. The period has been romanticized and sentimentalized by its violent climax. There is resonance in what Daniel Patrick Moynihan said to his friend, the columnist Mary McGrory, after Kennedy was killed and she commented: “We’ll never laugh again.”

“We’ll laugh again,” Moynihan replied, “but we’ll never be young again.”

While the outcome of the Vietnam conflict is indisputable, the looming and unanswerable question is what John F. Kennedy would have done if he had lived. The record of the Kennedy years shows that the humiliation of the 1961 Bay of Pigs fiasco in his first year in office, when the young president concluded that he had been misled by the CIA and the military, followed in 1962 by the Cuban Missile Crisis, when Kennedy overruled those who favored a military solution, likely would have meant that he would adhere to his belief that the war in Vietnam was up to the Vietnamese to wage – and not to be the object of American intervention on a vast scale.

Historians now generally agree that Kennedy was killed before he had made a conclusive decision about whether the U.S. would be out of Vietnam by 1965. Decades after the fact, McNamara was certain that this would have been Kennedy’s goal, but he never publicly went as far in his public statements as he did in sessions with his editors.

McNamara’s selection as secretary of defense was itself not predictable. He had only recently been named president of the Ford Motor Company in the fall of 1960, and did not know John Kennedy personally. When the president-elect offered him the job – on the recommendation of the Harvard economist John Kenneth Galbraith and former Secretary of Defense Robert Lovett, who admired McNamara’s demonstrated management skills and personality – McNamara said he was not qualified. But within days, the appointment was announced on the snowy steps of Kennedy’s residence in Georgetown.

Like Kennedy, McNamara was young, just forty-four when he took the reins at the Pentagon. He had no particular political affiliation (at the time of his appointment he was a registered Republican), but his manner exuded competence and confidence without arrogance – though, ironically, arrogance would later be considered his defining personality trait.

McNamara was not from the establishment elite, as was McGeorge Bundy, the new national security adviser. Though he had been to Harvard for graduate study, he spent his college years at the University of California at Berkeley. But over time McNamara grew so close to the Kennedy family that he was asked to be at Andrews Air Force Base when the president’s casket arrived from Dallas on the night of the assassination.

Parts Six Seven, and Eight cover the events of 1964 and the accession of Lyndon Johnson, who called himself “an accidental president.” Once powerful as the Senate majority leader, Johnson as vice president had been degraded politically and personally to the extent that he had intended to remove himself from the Kennedy ticket in 1964.

Yet suddenly he had the position and the power that he had sought for so long. From all accounts, he was resolved to be elected for a term in his own right in 1964 and use the power of the presidency to pursue what he called the “Great Society” – government programs that would make America the nation of its unfulfilled founding principles. McNamara and most of JFK’s senior leadership team made the transition to Johnson knowing that continuity was important after the shattering impact of Kennedy’s death.

One of McNamara’s strengths of character which had made him successful at Ford was understanding hierarchy and whose voice mattered most. So, as Johnson settled in McNamara made himself valuable, even in Johnson’s terms, indispensable.